Joan Didion and the Instagram Notebook

Sometimes, I think of Joan Didion when I use Instagram.

I always remember her words from On Keeping a Notebook – ‘it all comes back’ – and I’m often terrified. They’re heavy, the kind that Didion has poured into my feet so quietly, steadily, that it’s difficult to move. It’s easy to imagine her, sitting in a little bar across from a certain Pennsylvania Railroad Station in Wilmington, Delaware (not that I know what it looks like), scribbling into a notebook about ‘that woman Estelle’, while actually watching the woman in the plaid silk dress talking to a cat lying in a patch of sunlight. She writes about a familiar impulse: like the need to type a note on Keep while you walk to university, crossing the road at The Queen’s Head – London pavement flyer, An invitation to see things differently. Winter.

When a little later, Didion describes her notes as ‘bits of the mind’s string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage’, I can suddenly move again. I’ve also always kept a notebook; an invitation to see things differently – what I really meant was, I saw him yesterday, we sat outside the bar asking each other how much we’d written, we’ll see each other again today; there should be an on-off switch for this business of one-sided love.

–

My friends have often told me that I was late to the Instagram party. My first post, and I thought about it for a long time, was of my aunt’s dog Banja, and a cup of tea. Like every other morning, we are on the balcony at home in Bangalore. It’s early, and my tea is on a ledge, and you can see Banja looking up at something through the glass of an open window. The photograph is obviously (badly) edited. It’s captioned ‘Windows #1, Morning face’, and has 29 likes and 13 comments – mostly about how I’m finally on Insta – but my favourite, from a close friend: I knew your first post would be Banja or coffee or both.

I replied, and I’m quite sure I was grinning while I typed it, So well you know me. I meant it.

Except, and maybe it really doesn’t matter, I’m drinking tea and not coffee. But everyone knew then that I lived with my aunt, always talked about our (her) dog, and drank too much coffee, so I didn’t correct him – I mean, he knew my first photograph would be of Banja, or coffee, or both.

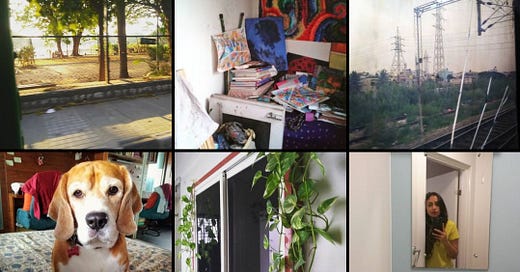

For some time now, I’ve been thinking about my relationship with Instagram. I’ve always been curious about how my friends use – and curate themselves – on it; I skim through their planned, choreographed photographs; the sudden, spur of the moment ones; their odd photographs of things only they’ve noticed. Then, sometimes, in the slow hour between late morning and lunchtime, I scroll through the photographs I’ve uploaded to Instagram. As of today, there are eighty of them, shifting between Hyderabad (home, where I grew up), Bangalore (home, where I worked and went to college), and London (home? where I went to university). I’ve added them since the end of September 2016 in sputtering starts and stops – the most recent are of Banja staring at me while I eat (caption: Chikki); the smudged view of Bangalore from a train window (caption: Sometimes it makes me so happy to know I’ll always, always come back here); the narrow, dusty reading room at home in Hyderabad that I used to paint in (caption: Renato Rosaldo, The Day of Shelly’s Death, followed too quickly by Max Porter, Grief is the Thing with Feathers ) – and I wonder what people see. I’m always wondering what people see.

Then, more and more, I think I’ve got it all wrong.

That in my permanently online condition of seeing and being seen; in the midst of what feels like the pointed sharpness of Twitter, and the expanding shapelessness of Facebook – neither of whose contours I’ve ever fully settled into – it’s my changing relationship with Instagram that’s constantly reminded me of my writing, and of my quiet. Often, I’m also, as Ariel Lewis writes, a ‘virtual wallflower, lurking on the edges of chatter’ – much like offline, where some people insist that I’m too quiet; where, when there’s a lull in conversation, friends from school turn to me, patronising, gracious, teasing, It’s okay, you can say what you’re thinking; in college, suspicious, It’s always the quiet ones you have to watch out for; in class, my teachers, She writes well, but she won’t speak; in all relationships, frustrated, I need to know what you’re thinking; at home, hurt, Are you always like this, or only with me? I’ve often wondered who I want them to see – these 344 followers, three-fourth of whom I haven’t spoken to in months, and at least half in years – until I tell myself that I should stop, that this is a rabbit hole, and notice that the self-absorbed spiral of this exercise makes me breathe deeply, bite my lips, crack my fingers with my thumbs.

But, quite vainly, I also know the answer, and this is where I come to Didion again – sometimes I want to say, look, here it is, here is a 23-year-old-trying-to-write-person-who-used-to-be-a-reporter-and-doesn’t-know-if-she-can-(or-wants-to)-be-one-again – except, how do you say such a thing aloud? What happened to being quiet, self-effacing, and knowing, as Didion writes, ‘that others, any others, all others, are by definition more interesting than ourselves’? Didion, I text my friend V, Didion’s helping me make sense of Instagram.

Here is a different scene. One of the many times we fought, and I’m glad we’ve never spoken to each other with the same bitterness since, we were sixteen, and I was home from boarding school for the holidays. My friend D was on the floor of my room, lying on her stomach and flipping through something I’d written in my circular, self-consciously good-girl handwriting for English class – something vaguely about me, my mother, my mother’s mother, and this girl and her mother – until she asked me, her words bristling as though they’d slipped into hot oil, So that’s it? We’re all going to keep being someone in your stories, then?

I remember an elastic silence stretching between us. I registered, for a brief moment, in the way that people tend to do in situations of cementing tension, a group of women singing happy birthday in the hospital canteen outside my window – until D, gesturing at my papers, muttered, the cold of her voice now settling into the bends of my ear canal, This never happened either. Obviously, I said, neither my mother, nor my grandmother were alive, and then, ten minutes later – You can’t make up things about real, living people, she declared, I don’t care if you call it fiction – and left.

D doesn’t remember this fight. But there’s a line in one of my notebooks, perhaps from a few months later, scribbled in the same circular, good-girl handwriting, You were born in a zoo (x2), with lions and tigers and monkeys like you, happy birthday to you – hostel, 2012. I remember the night. It was M’s birthday, and her roommates had made her a cake out of warm milk and crushed Hide-n-Seek biscuits; I was in the next room, there were torchlights, and they were singing this zoo version of happy birthday in hushed voices. Perhaps I wrote it down because it all came back: the cold silence that spread between us before D left – the rapid descent of my stomach to the floor because I thought this was it, our final fight; my confusion; the sharp sting of her words, ‘living people’ – expanding and folding, expanding and folding, and expanding and folding over itself. It happened, I now tell D, I’m sure it happened, but so what if it did, she wants to know.

As is often the case with my explanations, I don’t have a coherent answer; I only want to remember the shuffle of papers, the scraping of her slippers on the floor, the heat of her words at boiling point. And Didion writes of this moment precisely – first, ‘instead I tell what some would call lies’, and then, ‘how it felt to me: that is getting closer to the truth about a notebook’ – and I think, how it felt to me, that is getting closer to the truth of our fight that D doesn’t remember, and I will write about; that might or might not have happened, because it’s her memory against mine. Then, from the last month, there’s another note, Get lost, this isn’t your room, get out – three-year-old boy in a Spiderman t-shirt to aunt he doesn’t remember, and something else comes back. We are in Bangalore visiting my father’s cousins, and the point of this entry is really the boy’s father, looking straight at me while I sit quietly in a corner smiling at his son, saying loudly to anybody who will listen, be careful what you say around her, or she’ll write about you. It’s always the quiet ones you have to watch out for. Suddenly, I’m wondering what he imagines – she’s going to write about this too, she’s locking it away in the well-oiled filing cabinet of her brain in the drawer labelled ‘family’ – and I think of D, who first yelled, So that’s it? We’re all going to keep being someone in your stories, then?

I bought my second, tearing copy of Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem in 2014, when I lived in Bangalore. I found it at a second-hand bookshop, and only picked it up because its previous owner’s handwriting looked crushingly like my mother’s. They’d pencilled in something across the margins of nearly every page in the book – ‘talks to audience’, ‘a lot of feelings’, ‘typical mother’, ‘things are dying’ – and since I returned often to On Keeping a Notebook, I regularly re-read their terse observations. Where Didion wrote of her notebook, ‘Remember what it is to be me: that is always the point’, the previous owner had underlined and paraphrased, curving their f’s and r’s like my mother would have, ‘The disclosure is made to support the actual idea of the essay: although her notebook consists of random observations of facts and people, it’s actual subject is herself’.

And so, the actual idea of this essay, and perhaps here, Didion would disagree: Writing – my notebook was how I came to writing – trying to loosen the now tenuous link between my Instagram and writing. After all, it all comes back. The story I wrote some months ago – about two young women who move into an apartment together to write – is tinted by the memory of an old notebook entry, ‘They said we would get divorced in a year’ – two writers, still married in 2016 – a line I wrote down because I was 21, and thought I needed to remember what it felt like to want that kind of love. It is also tinted by a memory saved on Instagram: a photograph of my former office balcony on a Saturday, when the three of us sat down for an afternoon break, and they told me about their wedding.

But now, and it’s louder than before, I can hear my quiet. For the longest time, I wasn’t on Instagram. And then suddenly I was, posting nine photographs – of Banja, of another dog called Biscuit, and the dusty, deep green of trees that leaned into my office balcony – in fifteen days. Then there were sixteen posts over the next month, which quickly became seven, then six, and three, until I was skipping the months when I began to feel irretrievably unhappy. Here is an (approximate) inventory: there are four selfies; fourteen animals – eight of Banja, four of other stray dogs, two of skinny kittens I vaguely remember; one scarecrow I’d made in a park with friends; one bunch of helium balloons, the largest shaped like Winnie-the-Pooh; two protests in Bangalore at Town Hall, one of which I reported on; eighteen in London – my favourite seven of places I used to read at, captioned with the titles of books I’d read there; two others of snow, whose seeping, soaking cold I saw and felt for the first time. Then there are five posts of my friends – like the one of S unhappily doing yoga, one at breakfast with Z and S, one of (another) S pretending to fly; three of mornings without the keys to my former office; two from a trip to Silchar where my father and I got lost in the rain; one of Elena Ferrante’s The Days of Abandonment; six of swirling, sunlit windows, thoughtfully captioned, ‘Windows #1’, ‘Windows #2’, ‘Windows #6’.

And yet, what it doesn’t say: the now-archived photograph of a framed picture of my mother reminds me of the first time I spoke to my father about her death. I had messaged him from a bench outside university in London around the tenth anniversary of her death to say that I was thinking of him, and her, and heard the unexpected gentleness in his voice when he called me. The photograph of the roads outside my student accommodation covered in a layer of snow also brings it all back – an initial giddy happiness, and my father asking me on our weekly Sunday-morning call, What did the snow feel like? They will, I imagine, appear in some story I write many years later.

As of today, my last post is from October 2018, when I returned home from London and began to obsessively read about grief – a word whose weight I’m still hesitant to hold and examine, but record compulsively in my notebook (‘I always send my mother flowers on her birthday’ – London to Germany) – of women who’d lost their mothers, sisters, husbands, and children, and men who’d lost their mothers, fathers, wives. I skulk around on Instagram, watching my friends and acquaintances becoming doctors and architects, getting married, or spiralling and in pain, and like Lewis, I don’t always reach out. Other times, I scroll through friends’ profiles and see, clear as glass, that they are photographers, filmmakers, designers and writers – unmistakeable in how they see and display their worlds. Like with Banja and the coffee, and my unending photographs of perhaps unexceptional spaces, sometimes I still want to say, here is a 23-year-old-trying-to-write-person-who-also-used-to-be-a-reporter-and-doesn’t-know-if-she-can-(or-wants-to)-be-one-again, but, more than ever, my stomach begins crawling up to my throat. I try hard to let go of my quiet – It’s okay, you can say what you’re thinking – as though it’s as simple as untying a docked boat. But I have never untied a docked boat.

–

And so, I return to Didion, who writes: ‘Perhaps it is difficult to see the value in having one’s self back in that kind of mood, but I do see it; I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not’. More and more, I turn to scroll through Instagram and flip through my notebook to write, thinking, ‘How it felt to me’, ‘Remember what it is to be me’.

If I was to post a photograph on Instagram today, it would be of my room, and the corner I’ve been sitting in to write this – on the floor, against the wall, next to my table, with a blanket wrapped around my legs. What you wouldn’t see: the cupboard in front of me, taped with photographs of Z, S, and Banja; A’s postcard from Bhutan, and another of a yawning dog that’s captioned Bitch; two stickers from London, one for fair contracts for workers, another announcing ACAB; a lino painting from (another) A for my birthday, with Final Notations by Adrienne Rich written out neatly behind it. The photograph wouldn’t mean much to anybody else – like an older Instagram post of my room in Bangalore, or the statue of a ballerina in London – and, why should it? But as with our many selves in our various notebooks, it would all come back: the unexpected frustration of writing this, the worry that I’d been at it for a month, with nothing to show; the irritation that I’d even drawn a mind map in the hope that it would make writing easier. After all, even the photograph of the ballerina statue brings it back – October 2017, the cold day I met an old friend in a city I was new and lonely in. The statue reminded me of the agony in an opening sentence of a story by Angela Carter, ‘She was like a piano in a country where everyone has had their hands cut off’ – a line I’ve written down in my notebook, that now reminds me of what it felt like to be swallowed whole by a city I wasn’t sure I could grow to like. It’s like finding another entry in my notebook, Sometimes you can only be truthful in fiction – woman in Blossoms bookshop looking for Alice Munro – and thinking of D, who might have been the first to ask me, ‘So, that’s it? We’re all going to keep being someone in your stories, then?’